Container 101

What are Containers?

Containers take their name from their real-life counterparts. We can leverage a Container of any sort for this analogy. But the de facto standard virtualization is of course, the shipping Containers. When you are shipping items to the other side of the world, Containers make it easy to package goods together into a single shipment. The standard shape and size makes packing lots of containers onto a ship efficient. The walls provide isolation, preventing items from getting mixed together. Ther are portable, designed to be easily moved, and shipped, and there’s a clear separation of concerns.

Containers in virtual life, if you will, have very similar properties. Containers are essentially abstractions that provide a standardized way for you to package your application, its configuration, and dependencies together into one logical object.

These virtual Containers are standardized in both how contents are created, and largely how they expose resources to your application. The packaging provides a logical separation between applications. It also provides efficiency, allowing many applications to run inside a single host. They are portable, because all dependencies are packaged together with the application, providing a consistent Runtime Environment regardless of the target system, whether that’s an on-prem data centre, the public cloud, or even your local system.

What are Applications?

To humans, applications are software programs that are developed to perform certain tasks and execute on a computer. They are written in human-readable language and compiled into something that the computer understands.

To computers. applications are binary instructions that tell the computer how to execute tasks. The tasks are represented as processes in the operating system.

All computation is primarily based on managing the utilization of three key components of a computer, the CPU, Memory, and I/O, or input-output.

The CPU executes instructions, which is your application, on data that is read into memory from the disk or network, and access to these is mediated by the operating system, which manages how much of each resource is provided to each process or application.

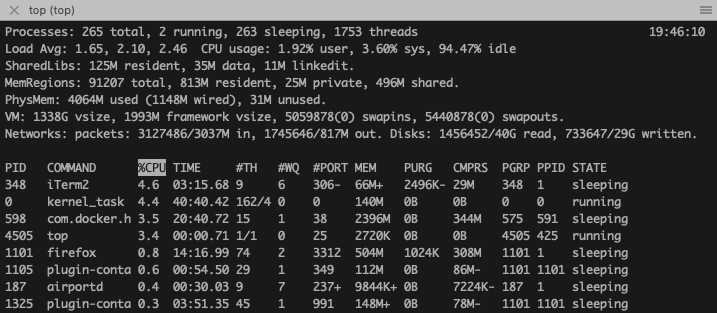

Below is an example of Top command on a linux based operating system, that displays all currently running processes.

Here we have a process identifier or a PID, that’s unique to each process. We display the CPU usage and a lot of resource information such as the state and the memory percentage used by that process.

So now that we understand applications a little bit better, let’s dive back into what a Container is and explain how that matters to an application, and how those things fit together.

Virtual Machines vs Containers:

It’s an unfair comparison to compare Virtual Machines and Containers because they work together quite commonly. But some of the distinctions are here:

So if we start off in building a Virtual Machine, we start off with Hardware and we have a Host Operating System. And then we have to install a Hypervisor. The Hypervisor is what allows you to divide up that single physical infrastructure into many smaller Virtual Machines. Within those virtual machines, you’re able to install a unique operating system(any operating system you like). Inside of that operating system applications can be installed along with their dependencies.

In the Container world, we start off from the same place, we have to have Hardware and Infrastructure and an Operating System. But we also now have a new component, the Container runtime. And of course, Docker is the most common Container runtime used today. In addition to the container runtime, now we have the applications and their dependencies and libraries packaged together. And this is only possible because the Container Runtime manages that packaging and is able to understand what a Container actually is and how that packaging works, and make that operate within the context of the Operating System. Container runtime doesn’t really care if it’s running on bare metal, or if it’s running on a Virtual Machine. Both options are possible and quite common.

Now that we have got a little bit of information, we can describe Container slightly differently.

A Container is a process which is extracted from tarballs of your applications and it’s dependency. It’s anchored to namespaces, which provides the necessary isolation we desire. And it’s controlled by cgroups, which helps us with resource utilization management.

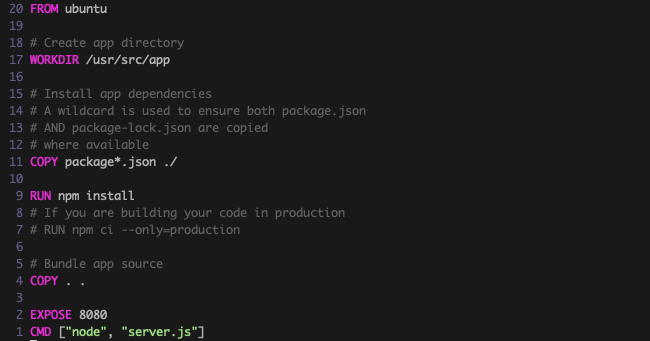

Now lets take a look at a Dockerfile which is the container specification. The Dockerfile provides a set of instructions for how you want your Container to be built and run.

In this example, you can see the base image is Ubuntu. We setup a directory, install some dependencies. We copy our source code. And then we define a port that allows us to expose the process to the outside world and finally, we run the application in this case node leveraging an application file called server.js.

The container run time is a client-server application. The docker command line uses an API to connect to the container runtime. And the container runtime actually performs all the work. When you execute a Docker build the Container runtime builds an image from the Dockerfile that you’ve already defined. That image can be stored in a Container Registry, so it is accessible to other systems. And a Container really is simply a runnable image. When you perform the Docker run, it takes that image, (the container runtime)unpacks it, and executes it as a process. A process like any other process on your operating system.

So, in conclusion, Containers don’t really exist. They’re abstractions and like most abstractions, they have the ability to be very good or very bad, and in this case Container Abstractions provide a lot of value.